90 Years Of Hiking History: MCM’s Celebration of Its 90th Anniversary

In the fall of 2024, the Mountain Club of Maryland will celebrate its 90th Anniversary. Starting in May 2024, we will hold a series of events to celebrate this event and share information about our history, and our accomplish over nine decades, with our members and partners.

Below, we have provided some facts about our original founding and early history. Each month, we will share more information about MCM’s history; through short articles that will be posted as news blogs and then added to this page.

MCM 90TH ANNIVERSARY BOOK AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOAD: JANUARY 2025

MCM has now consolidated its 2024 90th Anniversary activities in a single document that is now available to read or download from our website. The new publication, which is entitled The Mountain Club of Maryland: 90 Years On The Trail… And More: Our 90th Anniversary Celebration, includes information about the May 2024 Kinetic Sculpture Race and the anniversary gathering at the Howard County Conservancy last September. In addition, it includes members’ reminisces about their MCM experiences that they sent in as part of our MCM First Person exercise last year. Finally, the 13 articles about MCM’s history that were written as part of our anniversary program are all included. (Those individual articles are still available for viewing below.)

By consolidating all these 2024 activities into a single document, they can be more easily preserved as part of our history and also accessed by our members. You can open the new book to read and/or save it by clicking here.

90th Anniversary Articles

- 90 Years of Progress and Change: A Decade-by-Decade Overview of MCM’S History

- Who was Pogo Rheinheimer, and Why is a Campsite Named After Him?

- History of MCM’s Paw Paw Shelter: It was Fun while it Lasted

- Walking on Wednesday: The History of MCM Midweek Hikes

- World War II and the Mountain Club: Trains, Trolleys and Trucks

- MCM and the A.T. in the Cumberland Valley: A Tale of Three Trails

- The History of the Hike Across Maryland

- World War II and the Mountain Club: Trains, Trolleys and Trucks

- Gimme Shelter: A History of Mountain Club Appalachian Trail Shelters

- The History of MCM’s Role in Maintaining the Maryland Appalachian Trail

- Who Were Our Founders?

- Women in the Early Mountain Club

- The Disappearance and Rediscovery of the Center Point Knob Plaque

- The History of MCM Trail Sections in Pennsylvania

- Future Topics

- Our 90th Anniversary Celebration

90 YEARS OF PROGRESS AND CHANGE: A DECADE-BY-DECADE OVERVIEW OF MCM’S HISTORY

Below is a timeline of significant events and activities in the history of Mountain Club of Maryland over its 90-year history.

1930s

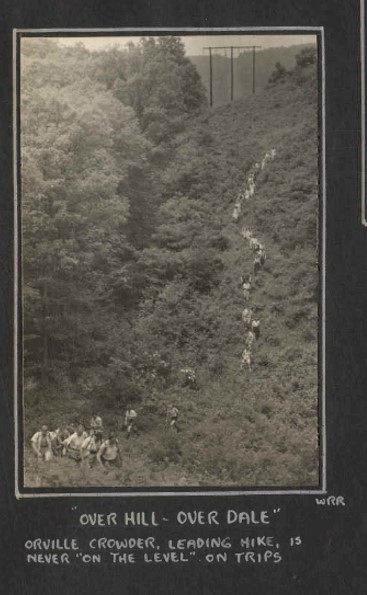

October 1934 – Orville Crowder led 27 hikers on a hike from Crampton Gap (now Gathland State Park) to Weverton Cliffs. At lunch the group discussed the formation of a hiking club.

December 1934 – The club was formed at a meeting at the Enoch Pratt Library. Crowder, Alex Kennedy and Osborne Heard wrote the MCM Club bylaws soon after the Dec meeting and a Trip Schedule was created.

January 1935 – The first official MCM hike was held in Patapsco Valley State Park.

First official club hike: PVSP, January 5, 1935

The club began hiking all around Maryland, PA, VA and WV. Most trips were on Saturdays, with occasional Wednesday or Sunday trips. There were groups focusing on photography, birding, wildflowers, etc.

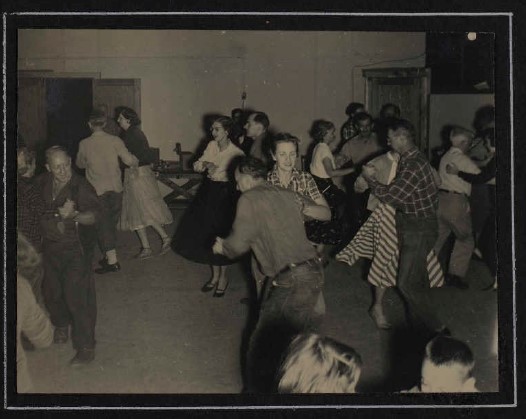

In the early years, there was typically one trip per weekend and at least one Saturday afternoon hike, one all day Sunday hike, and one overnight trip each month. There were canoe trips. rock climbing trips and ski trips. There were moonlight hikes, picnic lunches, group dinners, square dances.

1934 / 1935 – MCM took over maintenance of the Appalachian Trail west of the Susquehanna River. Within a few years, our assigned section was extended southward to its current end point at Pine Grove Furnace State Park.

In 1937 the club had 79 members—almost evenly divided between men and women.

Autumn 1935 – MCM placed the Center Point Knob monument in 1935 to denote the approximate center of the A.T. at that time.

October 1938 – MCM built its first hiking shelter (lean-to) in Dark Hollow on the A.T.

1940s

June 1940 – The MCM held the first Marathon across the Maryland A.T. with 21 hikers. Eventually, it would become known as the Hike Across Maryland (HAM).

1941 – MCM leased a cabin in Alleghany County from state of MD, naming it the Paw Paw Shelter or Town Hill Shelter. The shelter would serve as a base for hiking during most of the decade, despite ongoing issues with necessary repairs and vandalism.

Paw Paw Shelter, 1941

1942 – because of World War II gas rationing, MCM hikes were limited to locations accessible by bus, train, or trolley. A.T. maintenance work was extremely limited until 1944, when the rules allowed rental of trucks for work trips.

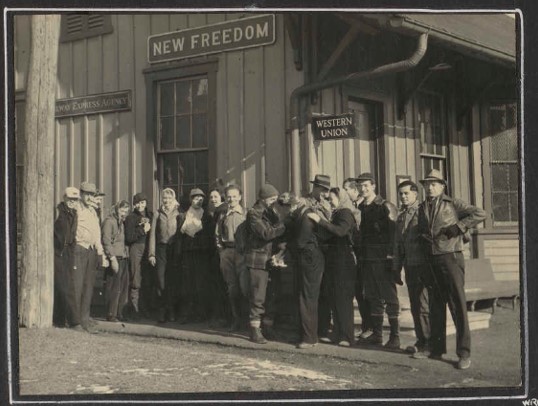

At the Train Station for February 1943 Hike

1942-1945 – About 15 Mountain Club members served in WWII.

1945 – Gas rationing ended and MCM was able to travel to more distant hike locations.

Many specialized hikes such as birding trips and moonlight hikes were halted during World War II and were not resumed after the war. Square dances were reduced in frequency to once each quarter. By 1949 they no longer scheduled these evening dances.

1948 – The Center Point Knob plaque was discovered to be missing.

June 1949 – MCM held the second Marathon hike.

1949 – MCM terminated its lease of the Paw Paw Shelter.

1950s

June 1950 – there were 149 MCM members.

1954 – Mary Kamphaus became the first female President of the Mountain Club.

1954 /1955 – In a major relocation of the A.T. through the Cumberland Valley in PA, MCM built approximately 15 miles of new trail on the A.T. between Duncannon and Boiling Springs.

1956 – The original Darlington stone shelter was built by Earl Shaffer and then maintained by MCM on Blue Mountain.

Catoctin Weekend – October 1954

1960s

1960 – The Thelma Marks shelter was built by Earl Shaffer and subsequently maintained by MCM on Cove Mountain.

Thelma Marks Shelter

June 1962 – MCM had 177 members.

At the June 1965 annual meeting, it was reported that MCM had conducted 41 hikes in the past year and that there were 196 members.

1970s

1970 – MCM served as host of the Appalachian Trail Conference annual meeting held in Shippensburg, PA.

May 1971- The third MCM Marathon hike was held. From then on, the Marathon / Hike Across Maryland (HAM) was held every two years.

March 1971 – there were 237 members.

1971 – The MCM Bulletin, which had been the name of the MCM newsletter since its inception, was replaced with a new, less voluminous, newsletter named the MCM News.

1972 – there were still overnight camping / hiking trips one weekend a month.

1973 – MCM began offering Midweek Leisure Hikes on Wednesdays.

1974 – 16-year old MCM member Pogo Rheinheimer drowns while canoeing on Potomac River. MCM establishes the Pogo Land Fund to fund a land purchase near the A.T. in his name.

1976 – MCM assumed responsibility for maintaining a section of the A.T. in MD from Wolfsville Road to PenMar, on behalf of the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club.

1976 – The two buildings of the Tagg Run shelter are moved away from its site near the stream to its current location about one-quarter mile away from the A.T.

1977 – A new prefabricated shelter, replacing the original stone Darlington shelter, is constructed at the current shelter location about a mile from the original site.

Prefabricated Darlington Shelter

1979 – A second set of Wednesday hikes (moderate), known as the Wednesday Walkers, is added to the hike schedule.

1980s

May 1983 – MCM had 341 members in May 1983.

1984 – The Pogo Campsite was opened for use by hikers.

1984 – MCM held its 50th Anniversary celebration with a dinner at Martin’s West and publication of the MCM First Person: 1934 – 1984 book. At that time the club’s charter members who were still living were Winslow Hartford, Alex Kennedy Jack Mowll, Fred and Grace Ward, and Ruth Lenderking Wormelle.

August 1986 – The MCM News was replaced by the Hiker High Points as the MCM newsletter.

1987 – Work began on a new 18-mile relocation of the A.T. through the Cumberland Valley in PA. MCM volunteers perform countless work trips over 4 years.

1990s

1990 – 1991 – The Alec Kennedy Shelter was constructed.

June 1991 – There were 534 memberships.

1991 – The new 18-miles Cumberland Valley section of A.T. completed; new Cumberland Valley club assumes responsibility.

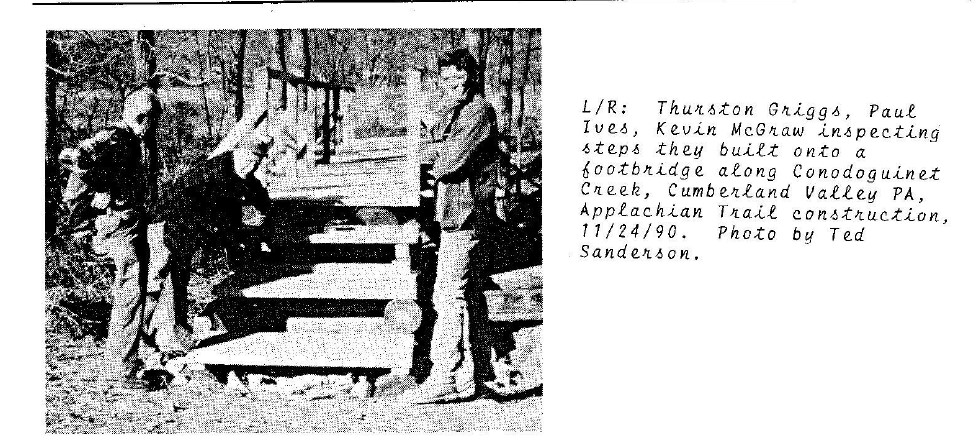

Working on the Cumberland Valley relocation

1998 – the old Tagg Run shelter (consisting of two lean-tos) was replaced by a new building named the James Fry Shelter at Tagg Run.

2000s

2000 – Cove Mountain shelter completed.

July 2001 – There were 866 memberships.

2002 – A bequest by long-time member Lester Miles led to creation of the Miles Fund. Since then, MCM has awarded more than $200,000 in grants for purposes related to hiking, trail protection and conservation.

2004-2005 – Construction of new Darlington Shelter was completed.

2006 – A third category of Wednesday hikes was added, known as “Tweeners” (because the difficulty level was in between the existing leisure and moderate/hard Wednesday hikes).

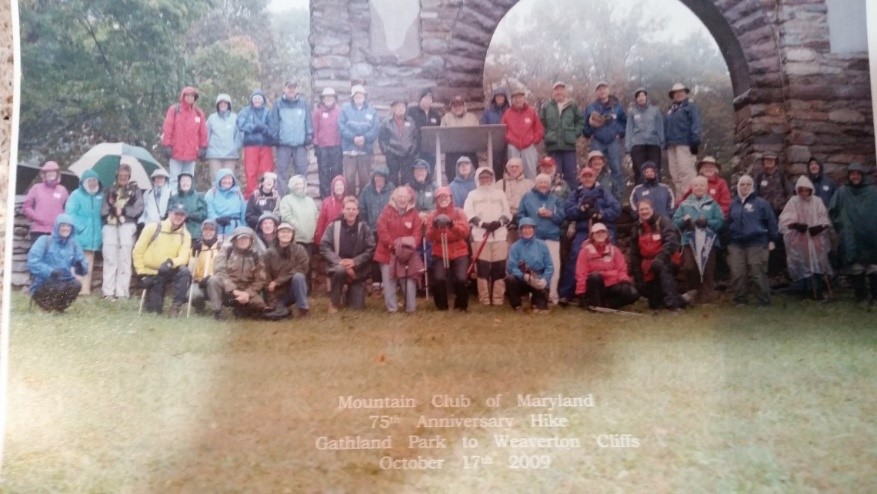

October 2009 – The club celebrated its75th anniversary at a 75th Anniversary dinner at Snyders Restaurant in Linthicum Heights. The club also repeated the original hike from Crampton Gap (Gathland State Park) to Weverton, and published the Thank You MCM: In Celebration of Our 75th Anniversary book.

75th Anniversary Gathering at Gathland State Park, October 2009

2010s

2010 – Center Point Knob plaque rediscovered. MCM donated the original Center Point Knob plaque to the A.T. Museum, after making a mold to allow its duplication.

2010 – A new privy was built at the new Cove Mountain shelter.

December 2011 – MCM had 722 memberships and 906 individual members.

2012 – MCM installed a duplicate plaque at Center Point Knob.

New Center Point Knob plaque

2015 – MCM co-hosted (with PATC) the ATC Biennial Conference in Winchester, VA.

2017 – A new privy was built at the Alec Kennedy shelter.

2020s

2020 – All hikes were cancelled during the spring of 2020 because of COVID public health precautions. For months after hiking resumed, hike sizes were limited to 10 persons and there was no carpooling.

2020 – Long-time MCM members Thurston Griggs was inducted into the Appalachian Trail Hall of Fame.

November 2020 – MCM led its first Meetup hike under its Mountain Club of Maryland Meetup Group program.

2021 – The Hike Across Maryland (HAM) was postponed till following year due to COVID. The HAM is now held in even-numbered years.

2023 – MCM added new category of Wednesday (Moderate+) hikes.

2023-2024 – MCM constructed a new A.T footbridge across Tagg Run in PA.

June 2024 – MCM grew to 902 memberships and 1143 individual members.

2024 – MCM’s celebration of its 90th Anniversary included a gathering at the Howard County Conservancy and entry of a float in the Baltimore Kinetic Sculpture Race in May.

WHO WAS POGO RHEINHEIMER, AND WHY IS A CAMPSITE NAMED AFTER HIM?

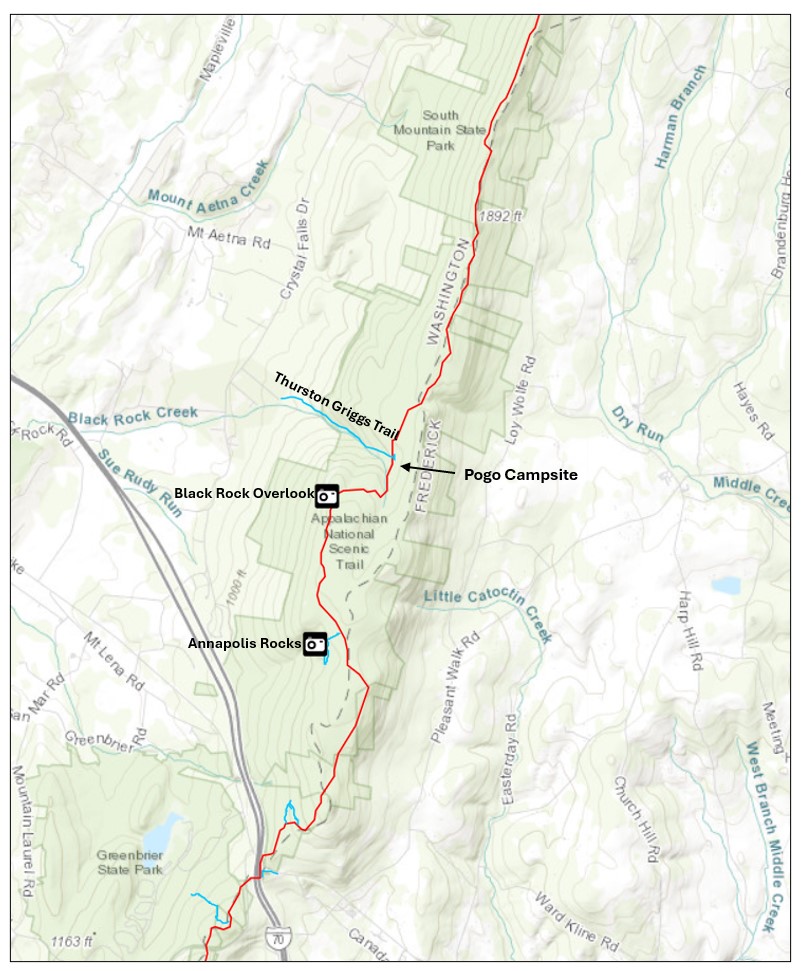

If you have hiked very far on the Appalachian Trail (AT) in Maryland, you are likely to have passed the Pogo Campsite, a hikers’ camping area less than two miles north of Annapolis Rocks, across from the intersection of the AT and the Thurston Griggs Trail.

Perhaps you have stopped to read the sign there:

Most Mountain Club of Maryland members who hike in that area know little of the background information about how and why that campsite was created and named. Here is the story.

Walter “Pogo” Rheinheimer was the son of Walter and Eloise Rheinheimer, both of whom were Mountain Club of Maryland members. Pogo’s father, the senior Walter Rheinheimer, was a dedicated MCM hiker. When he died in 2015 at the age of 98, his obituary stated that he had hiked with MCM for 60 years. Our records corroborate that he was a member of the club for at least that long. Walter was listed on MCM membership rolls as late as 2005. We don’t have membership lists for the early 1940s, but as early as 1943 he is listed in the Bulletin (our newsletter) as a member of the Excursions Committee that prepared the hike schedules. He served on that committee for several years. He also was also listed as part of the newsletter staff for a few years at that time, and his name appeared occasionally on the trip schedule as a hike leader in the later 1940s. Walter also was listed as responsible for Signs in the leadership list in the January 1947 Bulletin. After that, I did not find his name included in any of the club’s volunteer positions for several decades, although he may have been hiking with the club on a regular basis. I also found Eloise Rheinheimer (his wife) listed as a member of the club leadership as a Program volunteer for a short time in the 1960s.

Starting in 1982, Walter seemed to have become more active at the club leadership level again for a few years. His name was listed among the attendees at the MCM Council meetings for a few years, and he appeared in the minutes as taking part in various discussions. His name also appears in the leadership list as our Education Coordinator in 1983.

Their youngest son Pogo was an avid hiker and outdoors enthusiast, and was also an enthusiastic participant in MCM activities as a teenager. I found his name mentioned twice in the May 1974 Council meeting, when he was 16 years old. The first comment indicates that he was an active rock climber with our club:

It was felt that the rock-climbing group is moribund, since Lee Billingsley has moved to Boston and others have dropped, leaving only Pogo Rheinheimer. It was recommended that the new officers examine the whole situation thoroughly. Meanwhile Pogo will collect the equipment, most of which is already in his possession.

In addition, at that same Council meeting the Nominating Committee included Pogo as one of five names suggested as candidates for the three Councilor positions in the upcoming election. These two comments in the minutes show that he was already an active and respected club member despite his youth.

I found these photographs of Pogo on a website blog posted by his older brother Kurt, which can be found at this address: Kinship Remembered: Hiking With My Brother – Blue Ridge Country.

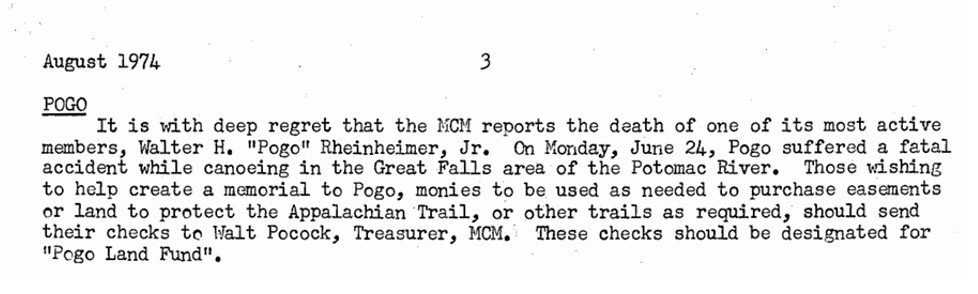

Sadly, Pogo died a month after the May 1974 Council meeting, a victim of a tragic drowning death at the age of 16 while boating in the Potomac River. (Since I started working on this article, I’ve learned from a couple of sources of a story that adds more sad irony to the events. Apparently, Pogo had planned to bike across the country that summer with a friend. When those plans fell through, he went canoeing on the Potomac River instead.)

NOTE: AFTER PUBLISHING THIS ARTICLE, I FOUND A 2009 NEWSLETTER ARTICLE WITH ADDITIONAL INFORMATION, THE BOLDFACED SECTION BELOW IS AN ADDITION TO THE ORIGINAL ARTICLE.]

More than 30 years later, in the February 2009 issue of Hiker High Points, an article written by Thurston Griggs provided more information about this accident:

Pogo had hiked more than half of the Appalachian Trail by the time he was 16. He was daring, adventurous, sturdy and inquisitive.

During the summer of 1974, he and a friend started out on bicycles from the Atlantic Coast to ride to the shore of the Pacific Ocean. On their bikes were side-swiped by a truck, and his companion…was hospitalized for several months…A neighbor pal, feeling sorry about Pogo’s disappointment…offered to take him for a canoe adventure on the Potomac River, starting at Harpers Ferry.

Pogo was not a swimmer – nor was he experienced with canoes. Before his life-jacket was securely fashioned, he stepped off-center into the canoe and became suspended upside in the water beneath the…canoe. The swiftly running water carried him downstream to his death.

The August 1974 edition of the News shared the new with our members, as well as MCM interest in creating a memorial for this young outdoorsman.

By November, the MCM Treasurer reported, the Pogo Land Fund had collected $559.00 in donations. That fund would increase gradually over the years due to additional donations and interest payments.

At the January 1975 Council meeting, Thurston Griggs read a letter from the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC) advising MCM to hold the Pogo Land Fund money until a procedure was established for purchasing land. (The Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC) was the official Trail maintaining club for all the AT in Maryland. It was not until the following year that MCM began maintaining a section of the Maryland AT on behalf of PATC.) Decisions about the disposition of the funds, which continued to grow slowly over the following years, would take a decade. Meanwhile, during the following years there were conversations at several Council meetings about possible land purchases using the Pogo Land Fund:

- At the February 1976 meeting, the Council voted to explore using the fund to “purchase a tract of land in a blue blaze trail near our shelter.” Presumably, this refers to the Devil’s Race Course shelter, because that is the only Maryland shelter for which MCM had any responsibilities.

- More than two years later, at the September 1978 Council, there was approval of a motion to purchase the “land discussed in a previousmeeting” (without specifying the location) for the Pogo Memorial Campsite. Notice of the intent to purchase the land was to be announced in the next club newsletter, along with a request for donations. The funds would be donated to the Appalachian Trail Conference (ATC) and then turned over to the National Park Service, which would acquire the site.

- The following month at the October 1978 meeting, it was reported that MCM received a letter from the National Park Service (NPS) stating its support for establishing the Pogo Campsite, but NPS was seeking a legal opinion before giving full support.

- At the February 1979 meeting, Thurston Griggs reported that NPS would not be involved in the campsite purchase because it was too far from the Appalachian Trail. (Again, the location of the proposed site was not identified.) According to Thurston, the PATC President had indicated that PATC might purchase a large tract of land in the area and would cooperate with MCM in development of the campsite.

There was no further mention of a land purchase in Council minutes or newsletters until the following year, when the September-October 1980 News reported that the property near Harpers Ferry, where the proposed Pogo Campsite was to be located, had changed ownership earlier in the year “after some protracted legal complications. One of the new owners had given preliminary approval of the idea of making the campsite available, before the legal complications arose. Thurston Griggs is trying to renew contracts and pursue the project.”

Once again, there was no mention of the proposed campsite for another year, then the October 1981 Council minutes included the following note:

Pogo Campsite – Two people bought land in the area; Bob Proudman has volunteered to try to locate these people and determine if they are opposed to the campsite. If there is opposition, we will have to look for another piece of land with a water source within reach of the A.T.

(Bob Proudman was an official with the Appalachian Trail Conference.) There is no additional information to indicate whether this is the same location as that discussed the previous year. Apparently, this possible site did not work out, because the following spring, the May 1982 Council minutes include a statement that:

“The State has suggested two other locations for the Pogo Campsite – one is off the trail below Annapolis Rocks and the other is near Rocky Run Shelter. Thurston will check these out.”

Thanks to the state of Maryland, a solution had been found. The next update is in the January 1983 Council minutes, where the Council is informed that the proposed Pogo Campsite location is the site of the old Black Rock Hotel—a hotel that existed in the nineteenth century. That location is about 1.7 miles north of Annapolis Rocks, so it may have been one of the possible sites mentioned the previous year.

THE INFORMATION BELOW IS ANOTHER NEW ADDITION TO THIS ARTICLE SINCE IT WAS FIRST PUBLISHED:

The February 2009 Hiker High Points article written by Thurston Griggs about Pogo’s death included more information about the circumstance that led to the establishment of the campsite:

…the State, at that time, was buying up land for permanent preservation, and it discourage private acquisitions because they might not all prove to be permanent. In that dilemma, Mrs. Ruth Blackburn, then President of PATC…suggested that the old Black Rock Hotel site (where there was a good water source on the Trail) be designated “Pogo Campsite” as a memorial to the young adventurer. And a pit privy became the sole amenity if offered to hikers.

The following month, at the February 1983 meeting, the Council was information that NPS had accepted Black Rock Spring as the Pogo Campsite, and that PATC had joined MCM in sponsoring the campsite. However, there were still issues to be worked out. According to article in the October 1983 News, it would be necessary to postpone the installation of a privy at the campsite until the following spring, apparently because of road access to the area that could abuse (vandalize?) the new privy. The state of Maryland was working on arrangement to prevent vehicle access.

It seems fitting that the side trail that intersects the A.T. right at that location has since been named the Thurston Griggs Trail, given Thurston’s work over a decade on the establishment of the campsite.

Two months later, the December 1983 News announced that the privy hole had been dug at the campsite and the privy had been designed. The article also solicited volunteers and a pick-up to help install the privy in late March 1984. The February 1984 newsletter reported that the privy had been pre-fabricated and was ready for assembly at the Pogo Campsite in the spring, and that South Mountain State Park had offered to provide transportation.

At the May 1984 Council meeting, Thurston Griggs announced that the Pogo Campsite was now completed and in use. The State Park would be installing five locked metal gates in the future to prevent motor vehicles from accessing the campsite. A year later, Thurston reported at the May 1985 Council meeting that the privy had been vandalized and that the state park had gathered materials for repairs. Apparently, the gates had not yet been installed, because there is a mention that the state had prepared the foundations for installations of the gates. (The privy was vandalized again a year later, and the article in the May 1986 News stated that the park had now closed off the roads that allowed vehicle access to the site.)

Here are a couple of photos of the campsite location:

Meanwhile, at the May 1985 Council meeting, there was also a discussion of how to use the Polo Land Fund–because the Pogo Campsite had been placed on state park land, the fund had not been used to purchase property. Here are the notes from the Council discussion.

Concluding Thoughts

It took ten years for the Pogo Camp Site, honoring an MCM hiker who died far too young, to be accomplished. The discussions at Council meetings indicate that several possible sites for land purchases were explored, but these options all fell through. From the information in the records, it is not completely clear how the campsite came to be located where it is in South Mountain State Park, but this entire effort involved cooperation by the Mountain Club, PATC, NPS, and ATC, and especially the state of Maryland for providing the site location.

In a blog titled “Commemorating Walter Rheinheimer” that can be found at Commemorating Walter Rheinheimer – Blue Ridge Country, Pogo’s brother Kurt described a family gathering in 2015 to commemorate their father. According to the article, they camped at the site and scattered Walter’s ashes there “at the site honoring his youngest son…”

Although I have never camped there, I hike past Pogo Campsite several times every year. Now, knowing more its history, in the future I’ll be a little more thoughtful and appreciative of two dedicated MCM hikers—one who spent most of his life as an MCM member, and one who did not get the opportunity to do so–and of all the work that MCM and its partner organizations went through to honor one of our own.

HISTORY OF MCM’s PAW PAW SHELTER: IT WAS FUN WHILE IT LASTED

It will come as a surprise to most of our members to learn that MCM once had a shelter for its own use in western Maryland. It was a long time ago, and while our records document many fun activities at the shelter, there were a lot of problems and a lot of work was expended maintaining the building. MCM dropped the effort after eight years. I’ve seen the Paw Paw shelter mentioned in a few old newsletters, but I didn’t know anything about it. So, as part of my 90th Anniversary research into aspects of our history, I’ve recently learned more. Here is the story.

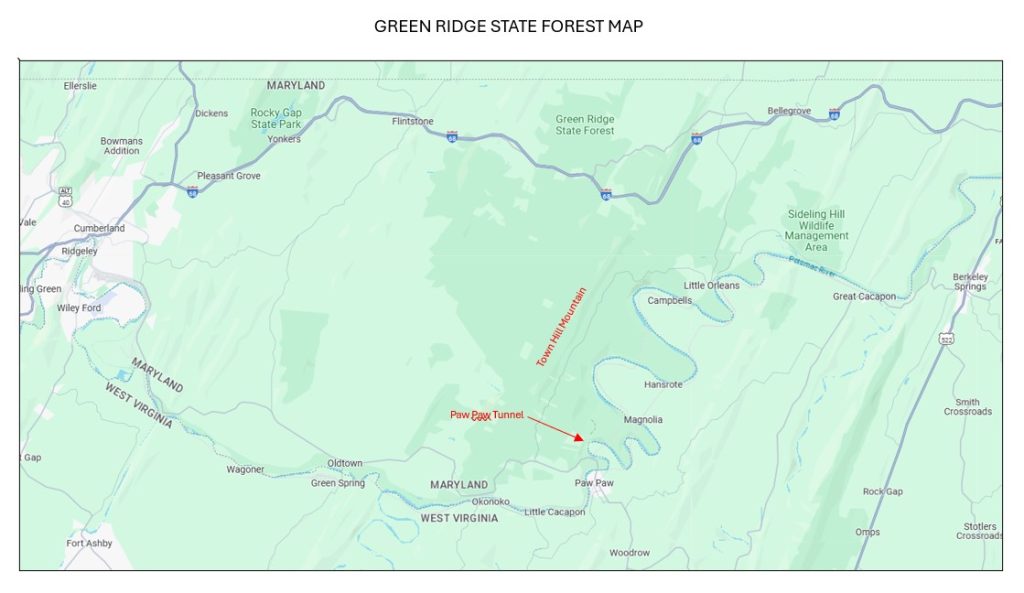

Apparently, the “shelter” was a cabin previously used by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). It was located on Town Hill Mountain in the Green Ridge State Forest in Allegheny County, in the southern part of the Forest in the area near the Paw Paw Tunnel (which was named for the small town of Paw Paw, West Virginia). Our records do not describe the exact location of the cabin, but here is a map of the area:

Based on information printed years later in a 1947 MCM Bulletin, the shelter was “140 miles from Baltimore via Paw Paw and 130 miles via Route 40, the first route having less dirt road and being less complicated. The shelter is located in an extensive mountain area which invites exploration, but is not provided with a marked trail system.” We know it was located on top of te mountain or a steep ridge because of later descriptions of difficulties driving up to it.

When the CCC’s use of the cabin ended, the Maryland (MD) Department of Forests and Parks offered to lease it to MCM. The first record I can find about this opportunity is February 1941 Council meeting minutes:

As chairman of the Shelter Committee Mr. Crowder described the shelter in the Green Ridge Forest near Paw Paw and how the State will lease it to the Club, rent for the first year to be the cost of improvements… The Council voted to contract with the State for the use of the shelter and authorized expenditure by the Shelter Committee of up to $100 on fixed improvements and up to $100 on movable equipment.

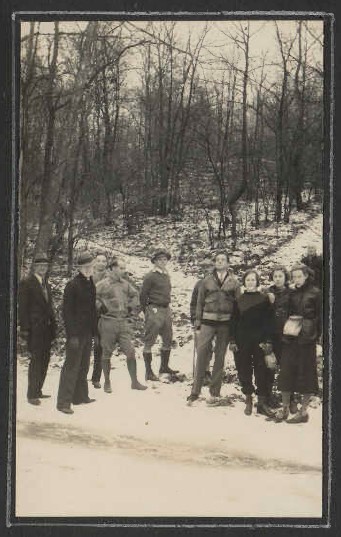

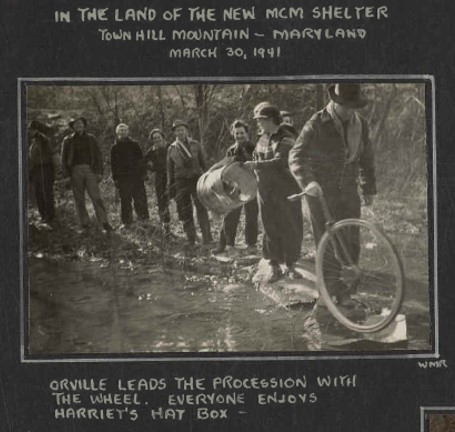

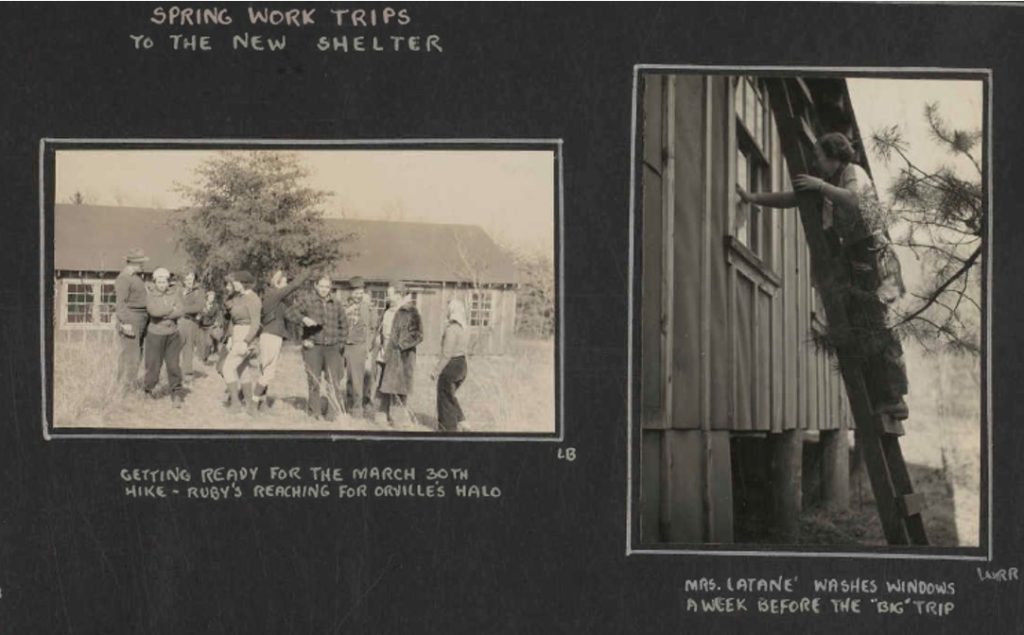

Basically, MCM would be allowed to rent the cabin for free if we paid for maintenance and repairs, or any improvements we wished to make. A group of club members must have visited the area a month later to check out the situation, because the photo scrapbooks has this photo dated March 31, 1941:

The condition of the cabin was apparently satisfactory enough to capture their interest, and we can imagine that the opportunity to have its own mountain retreat was enticing to the club. Soon afterward, at the April 1941 meeting, Crowder read a letter from the state verifying the arrangement. MCM could now submit plans for improvements to the building. Crowder named it the Paw Paw Shelter, and that is the name that MCM mostly used; but there was disagreement about the name among club leaders, and our records sometimes also referred to it as the Town Hill Shelter, and rarely as the Green Ridge Shelter.

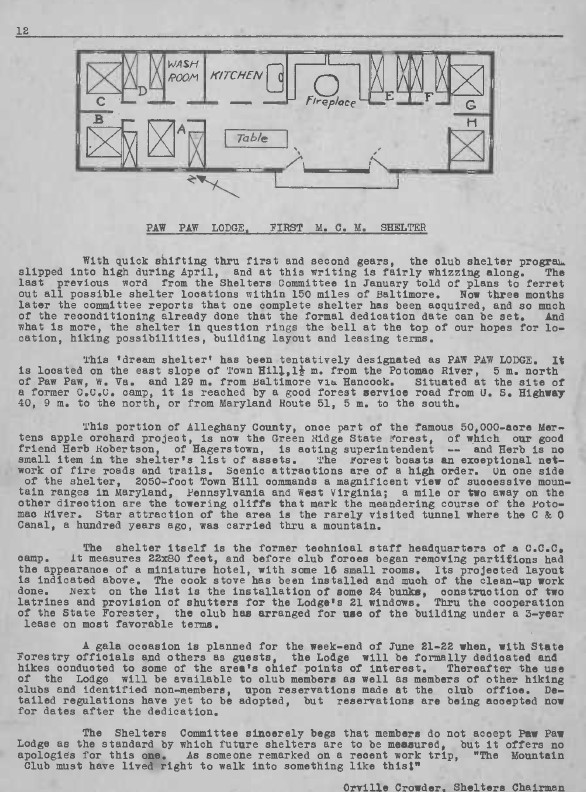

The new agreement was announced to the club in the April – June 1941 Bulletin as part of a brief summary of recent Council decisions. In that same newsletter, the trip schedule announced an overnight hiking trip there for the dedication of the shelter on June 21-22, as well as a hike of 10 miles (to the village of Town Hill) or 15 miles (to the Paw Pay Tunnel) on Sunday.

This newsletter also contained the following full-page article by MCM shelters chairperson (and previously the club’s first president) Orville Crowder, which included a floor plan. In that article Crowder named the cabin the Paw Paw Lodge, and states that the Mountain Club would install 24 bunks. (Later writings mention 26 bunks.) He said the Lodge would be available for members of MCM and other hiking clubs to reserve. It was rustic—it did not have running water (there were outside latrines and a spring nearby), and I assume there was no electricity although our records don’t mention the use of lanterns.

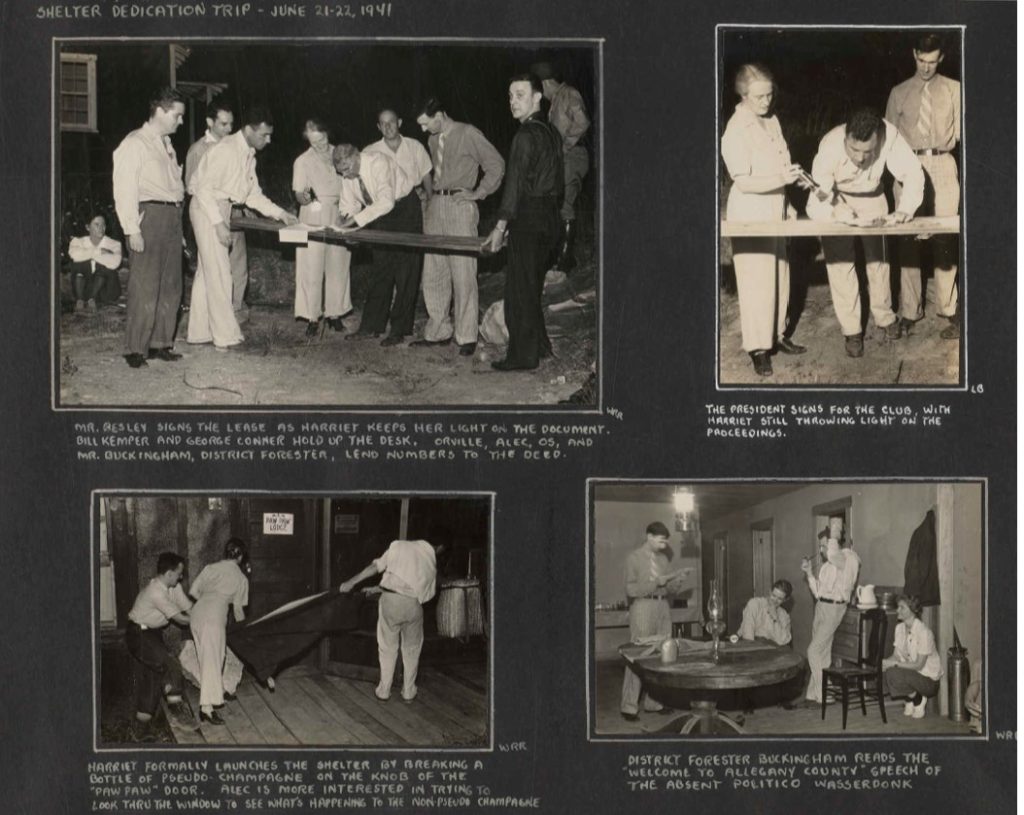

At the June 1941 Council meeting, it was reported that MCM members Crowder and Hicks met with a MD state official and were given the lease for approval by the club. The Council decided that the lease would be signed at the dedication ceremony. The Council was told that 12 bunks had already been installed.

A week before the planned dedication–on June 15–a group of club members visited the shelter for a work trip to prepare for the dedication. Perhaps that is when the first 12 bunks were installed. Here are a couple of photos from the MCM photo scrapbook for 1941, with the cabin visible in the background.

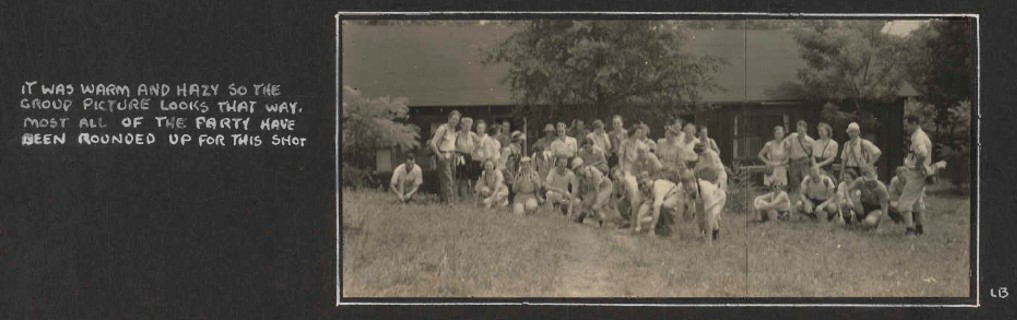

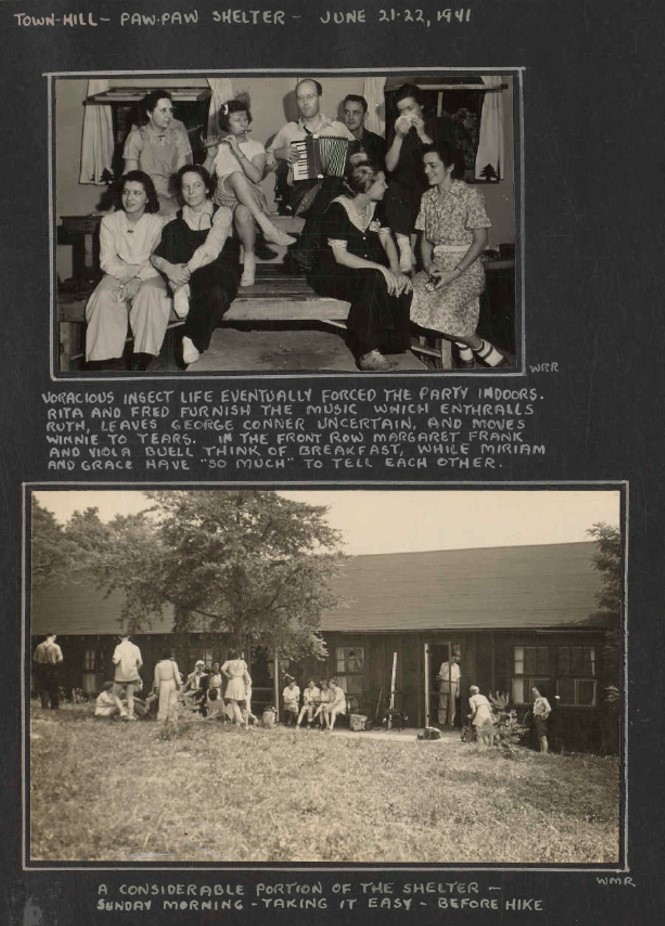

The MCM photo scrapbook includes more than 20 photos taken during the June 21-22 dedication weekend, which was attended by a very large number of our members. Some of them are typical Mountain Club hiking photos, but I have included some photos below that are most relevant to the shelter. There were far more attendees than bunks, so the many of them must slept have on the floor or under the stars.

(It’s worth noting that, according to an article in the Bulletin written several years later, two bottled of champagne were broken at the dedication because there was disagreement about the name of the shelter. One group christened it the Paw Paw Shelter, another group christened it the Town Hill Shelter.) After the dedication, the July – September 1941 Bulletin gave club members more information about the plans for the shelter: MCM had signed a three year lease with the state, under which MCM would pay for the necessary repairs and improvements. MCM set aside $200 for remodeling and equipping the building. Crowder stated that he expected the fees for use of the shelter (25 cents per person per night) would cover any excess costs. There would be 12 bunks with mattresses and 16 bunks without mattresses, so capacity would be “nearly unlimited”

Soon afterward, at the July 1941 Council meeting, the Council was told that club officials had investigated the possibly of insurance coverage for the shelter and were told that “the MCM Shelter is practically uninsurable. The question of legal liability was left open for future investigation.”

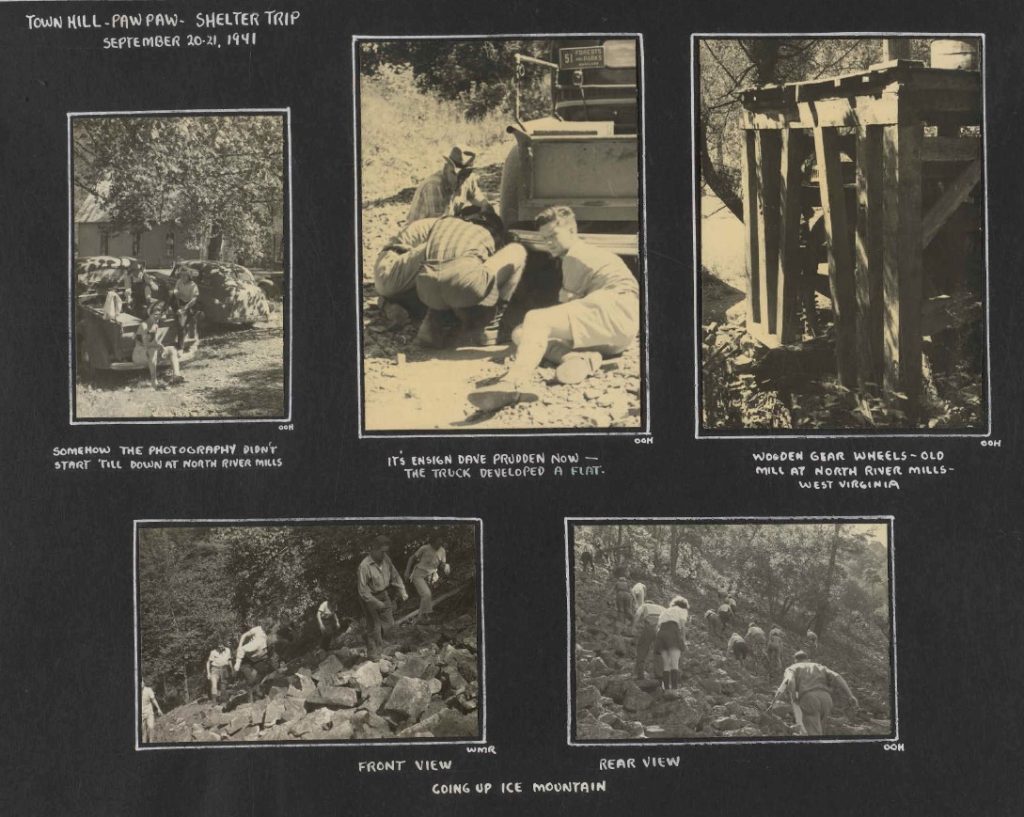

The next mention of Paw Paw is at the September 1941 Council meeting, where it was commented that, “The necessity of additional work to complete Paw Paw Shelter was discussed and it was suggested another work trip be held to finish up all work and make the shelter habitable before winter.” The photo scrapbook contains the following page of pictures of a September 20-21 trip.

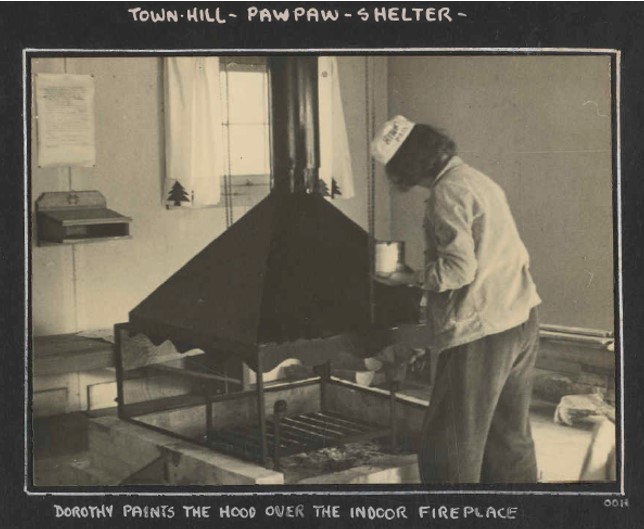

At the next (October) Council meeting, it was announced that there would be another work trip to the shelter soon, bringing all necessary tools and equipment to make it habitable for the winter. There was agreement that a stove would be needed, and the Council approved funds to buy a stove. The photo scrapbook has the following single photo from a work trip there in November 1941, showing that MCM had installed some kind of heating stove with an overhead vent hood.

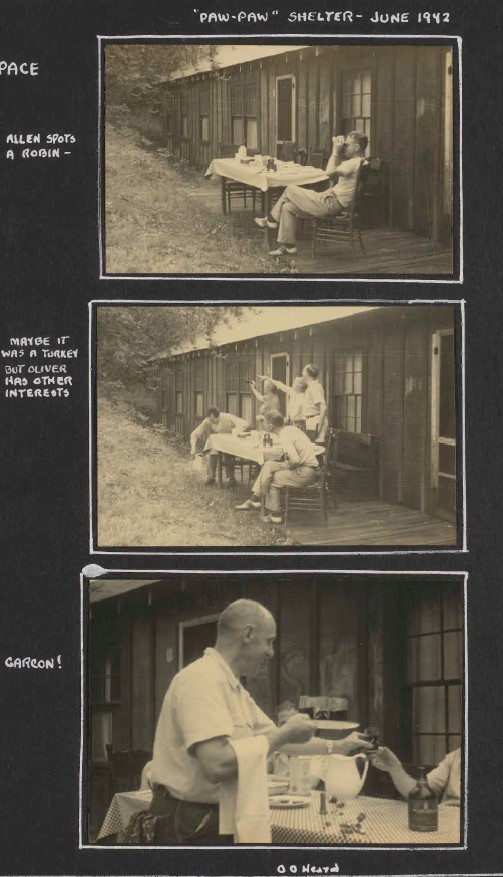

It appears that the club may not have visited again until the following June, because the next mention I found in the records is a photo of a June 1942 visit to the shelter:

However, members must have been reserving it for their own use because at the July 1942 Council meeting, it was announced that the shelter was being widely used and that shelter fees were “literally pouring in.” (It seems surprising that the newly imposed system of gas rationing would not have limited the club’s ability to reach the shelter, but they could probably reach the general vicinity by train—or possibly the gas rationing had not fully taken effect yet. There may have been regular use by members, other than club trips, that is not reflected in our Council minutes and newsletters. But it seems probable that use of the shelter would have declined after mid 1942 because of the gasoline restrictions.) It was also reported at the Council meeting that the water supply there was not good and that water should be boiled or treated with Hazeltone tablets before drinking.

At the November 1942 Council, someone reported that the Paw Paw shelter was in excellent condition except the front porch, which was in bad need of fixing. The Secretary was asked to see Mr. McCabe about fixing the porch. (The “Mr. McCabe” mentioned in these minutes was a nearby resident who helped MCM by keeping an eye on the shelter. He may have been keeping an eye on the shelter, but he probably wasn’t doing repair work, because the porch continued to deteriorate.)

Unfortunately, a year later at the October 1943 Council meeting, Orville Crowder reported that McCabe would no longer be able to look after the lodge after November. They decided to search in that area for a neighbor who would take on the role. Meanwhile, larger issues were raised at the November 1943 Council meeting:

Our biggest problem at present is what to do about the shelter at Paw Paw. There is a likelihood of losing the present site of the camp since a Prisoner of War camp is under consideration for location in Green Ridge Reserve. Mr. McCabe was unable to suggest anyone to over-see the property and Miss Lenderking reported on her visit two weeks ago there was indication that beetles we retaking over. Our lease expires in June 1944. Mr. Heard will write or see Mr. Kayler about what use could be made of the property in order to keep it from theft and vandalism.

The “Mr. Kayler” (sometimes spelled Kaylor in other documents) mentioned in the report was the official at the state Department of Forests and Parks who had responsibility for leasing the cabin to MCM.

In the Oct-Dec 1943 Bulletin, the newsletter provided an update on the status of the shelter. Four club members had visited the shelter in August and found the inside clean and tidy, and the latrines were in good condition. However, the outside showed need of repairs. The porch was badly rotted and fell through in several places when stepped on. The visitors made makeshift repairs to the porch and to rusted screens doors using available materials. They also stated that Mr. McCabe had been successful in keeping trespassers away. (The last sentence in the report suggests that possibly Mr. McCabe had continued to watch over the facility, but later reports indicate that was no longer the case.)

At the December 1943 Council meeting, Os Heard reported that the state did not believe a prison labor camp in the area would jeopardize MCM’s lease. A few of the Mountain Club members (Miss Caspari) planned to visit the shelter over New Years and bring home some equipment. The sporadic nature of the visits mentioned in the Council minutes seem to confirm that gas rationing had reduced the ability of members to use the site.

During the following year, there were several mentions about problems renewing the lease with state and keeping on eye on the shelter because of its remoted location:

- At the January 1944 Council, there was mention that an identified person was considered renting Mr. McCabe’s home, and would consider keeping a watch on the shelter for a fee. There was also a suggestion of a joint MCM and Glenn L. Martin spring trip to the site.

- At the July 1944 Council meeting, it was reported that a man named Joe Belford had moved into the McCabe house and that MCM would contact him about watching the shelter.

- At the September 1944 Council meeting, Orville Crowder said he was attempting to contact state officials at Annapolis about renewal of the Paw Paw Shelter lease, which technically had expired in June. The MCM treasurer, Merle Heart, reported that Joe Belford (the neighbor) was willing to keep an eye on the shelter, and the Council expressed willingness to grant him $10 a year for the service.

- At the November 1944 meeting, Crowder indicated the shelter lease was not resolved, and there was no resolution by the January 1945 Council: “Mr. Crowder has not received a reply to his letter to Mr. Kayler at Annapolis. Mr. Crowder requested an extension of the lease until after the war or until the resumption of traveling privileges will enable us to use the shelter.”

However, in the April – June 1945 Bulletin, Crowder informed members that the State Department of Forests and Parks had extended MCM’s agreement for the use of the Paw Paw Shelter building until six months after the war. He added that the Shelters Committee would arrange an inspection and work trip during the spring.

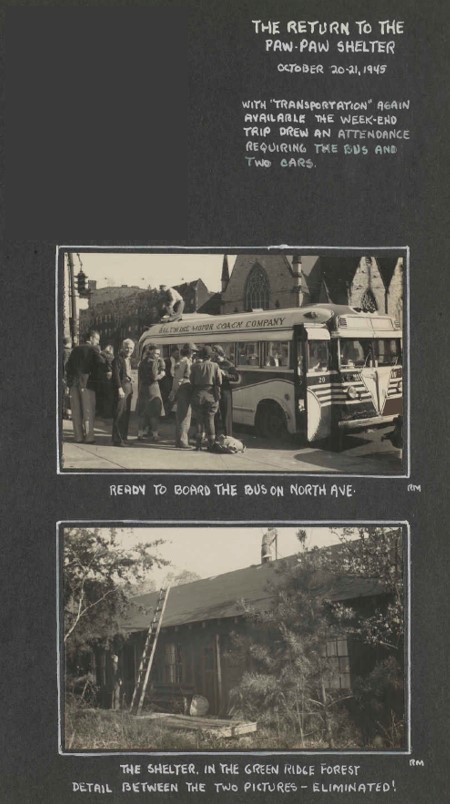

At the August 1945 Council, Os Heard proposed a bus trip to the Paw Paw shelter on October 20-21.

At the September 1945 Council meeting, Crowder suggested a group of MCM leaders should go to Annapolis to discuss the shelter lease—suggesting that the agreement mentioned in the spring Bulletin had not been formalized. He also suggested a work trip to conduct repairs on October 19 or 20.

The October -December 1945 Bulletin included an announcement of a work trip on October 20-21. There was also a brief report that four members spent the week of June 24 at the shelter and found the place little changed since the previous year. “There are a few more small leaks in the roof—though none of them are serious. The porch has rotted a little more and the cellar steps aer rotted beyond use… There was no evidence of anyone attempting to molest the place.” The report also stated that the McCabe house was being torn down and after September 1 there would be no one to keep an eye on the property.

At the October 1945 Council meeting, Mr. Hartford reported that MCM was able to get a bus and 22 persons had signed up to go to Paw Paw, and some might drive up in cars. “There was quite a bit of discussion about the bunks, would it be that those in the bus would be first to be considered for the bunks or would the gentlemen give way to the ladies…It was decided that the ladies in the bus first, ladies in cars, next, and gents in the bus and gents in the cars. A poll was taken on the approximate number of prospectives that might use the starry sky as their roof and it was felt that there would be sufficient bunks for all those who cared to sleep indoors.”

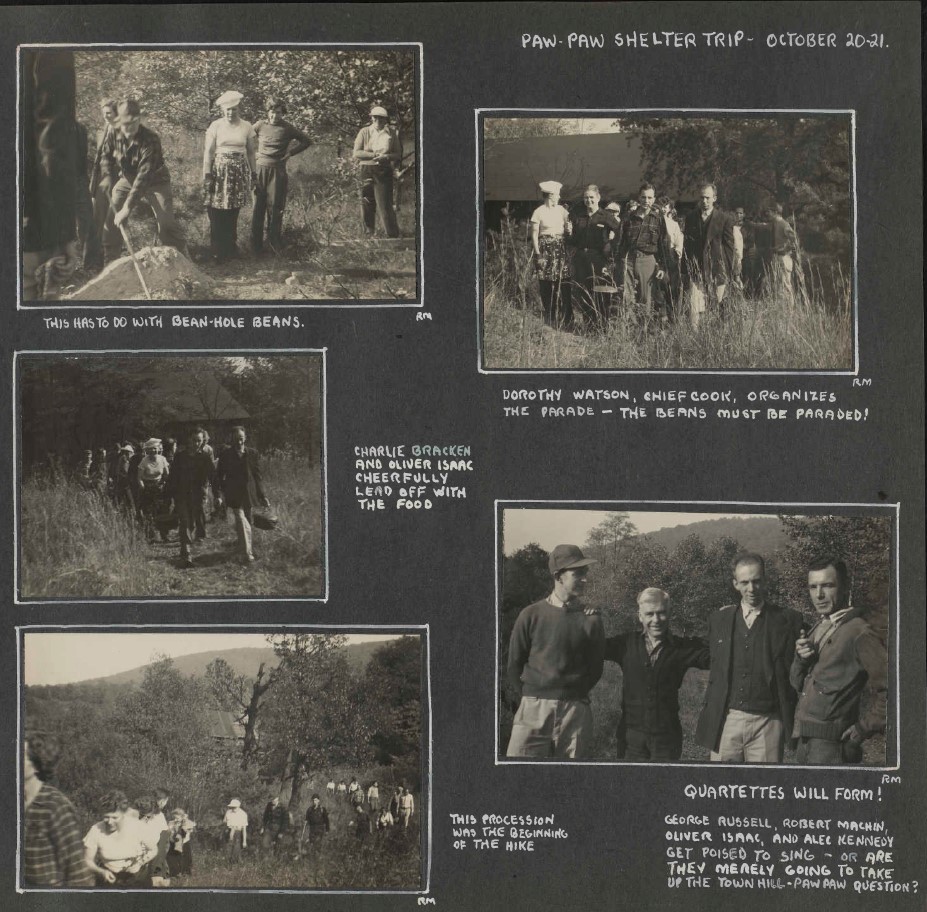

The January – March 1946 Bulletin included a report on the October trip. When they reached the dirt road leading to the shelter at dusk, the bus could not climb the steep hills. On several occasions the riders had to leave the bus and then it would back down to get a running start to reach the top of that slope. Eventually they arrived at the shelter. After a dinner prepared by earlier arrivals (involving cooking a crock of beans in a hole), they enjoyed a perfect moonlight walk, then a square dance. Some of them slept under the stars. The next day they hiked to the Potomac River and crossed to West Virginia on a railroad bridge to the point to the point where they met the bus to return to the shelter. Once again, the bus could not climb the last hill until the hikers were unloaded. After a meal, they climbed back on the bus for a nighttime ride back to Baltimore.

There are several photos of the October 20-21 work trip in the MCM scrapbook.

Once again, during the following year there were multiple Council discussions about the lease, and now there was an added problem caused by break-ins and thefts:

- At the April 1946 Council meeting it was reported that MCM member Ruth Lenderking had encountered MD State Forester Kayler on the street and had raised the matter of the Paw Paw lease. Kayler told her he would like the building to be used by more than just MCM. Kayler had declined invited to attend a Council meeting but was unable to come, so the Council agreed to try to set up a meeting with him in Annapolis. They also discussed the possibility of finding another shelter site elsewhere. As we will see, MCM took Kayler’s comment seriously, and over the next couple of years the club worked to make the shelter available to other groups.

- At the May 1946 Council meeting, Os Heard reported that on his last visit to Paw Paw, he found that the shelter had been broken and that tools, small pans, lanterns and some curtains had been stolen. That information was reported to club members in the July – September 1946 Bulletin, which also stated that the club was scouting another possible shelter site somewhere north of Chambersburg, PA.

- There was another discussion of Paw Paw at the October 1946 Council. Orville Crowder announced that he had arranged a meeting with Kayler on October 22, and he would be accompanied by members of the club’s Public Relations Committee. There was discussion about whether MCM wanted to spend money on repairing existing shelters or erecting and maintaining a new one. They also discussed the condition of the Paw Paw building and the water supply, how to protect it from vandalism, and how to increase its use.

- At the November 1946 Council meeting, Crowder reported on his meeting with Kayler: (1) the state was willing to continue renting the shelter to MCM but would prefer a three-year lease; (2) Kayler suggested that posting signs might reduce the vandalism problems; (3) the state could not help solve the water supply problem, and (4) MCM must show use of the building or the state might move it elsewhere.

- The MCM treasurer, Merle Heart, informed the Council at the November meeting that since May 1941, the club had spent $293.55 for equipment for the shelter and collected $122.00 in shelter fees, representing a loss of $171.55. He estimated another $100 would be needed to re-equip the shelter, and there was no assurance that vandalism would not continue. Several Council members were asked to inspect the cabin again and report on what repairs were necessary.

- At the December 1946 Council meeting, an MCM member reported that he had visited the Paw Paw Shelter and found that the ceiling was water soaked, the front porch needed extensive repairs, and the front door lock must be replaced. The firewood supply and various buckets and wash basins were still there, and some dishes, but he could not tell if some dishes had been taken. There was considerable discussion about whether MCM should continue leasing the shelter, followed by a vote on whether the continue leasing the shelter. They voted to continue the lease for the time being, but directed that the club should make an effort to increase its use.

- At the January 1947 Council, Heart stated that MCM had sent a letter to Kayler asking that No Trespassing signs by posted at the shelter. At the April 1947 meeting, it was reported that someone had visited the shelter and found four bare spots [roof leaks?] and 2 broken windows. A trip was planned to make repairs.

The January – March 1947 Bulletin had a short article informing members that the Council had decided to accept the state’s lease offer and retain possession of the shelter on a maintenance basis. It then discussed the need for repairs and the vandalism problems. The article also encouraged use of the facility by MCM and other groups.

At the May 1947 Council, a letter from the MD Department of Forests and Parks was read, which indicated that the state would be willing to let MCM continue using the Paw Paw Shelter for a fee of $10 per year and maintenance. The Council advised that MCM’s reply should suggest that the state inspect the site, post signs, and repair the spring. The Council also would inform the state that it had reached out to other groups such as the Maryland Ornithological Society and the Department of Education about using the shelter. There was discussion of what tools and materials should be brought to the shelter to make repairs.

The July – September 1947 Bulletin had a detailed article describing a work trip to the shelter on May 30–June 1, 1947, with 25 volunteers. All noticeable roof leaks were patched. The rotten front porch was removed and stones were taken from an old stone wall to make a stone terrace and steps. Broken windows were replaced. Afterward there were impromptu hikes, with a square dance after dinner. On the following day (Sunday) the group enjoyed a hike of around 10 miles.

At the September 1947 Council, it was reported that the Department of Recreation wished to reserve the shelter on September 27-28. A work trip was suggested on October 4-5 to fix the roof (so apparently the June trip had not found all the leaks), and erect signs stating that the shelter is a state-owned building.

The club’s efforts to find other groups to use the shelter had some success. At the October 1947 Council, there was discussion of a request by sportsmen at the Glenn L. Martin plant asking to rent the Paw Paw Shelter during the hunting season from November 15 to December 1. The Council directed that they should follow the same reservation procedure used by MCM members. Meanwhile, at the November 1947 Council meeting, the Council approved an agreement allowing the Marco Hunting and Fishing Club (a Baltimore area club) to use the shelter during the period November 15, 2047 thru January 1, 1948, with the exception of Thanksgiving weekend. The proposed usage by that group did not deter MCM from conducting two large visits that fall, both described afterward in the January – March 1948 Bulletin:

- MCM members enjoyed a Halloween party / work trip from October 31 – November 2, 1947. The article discussed the process of preparing bean-hole beans (cooked in a stone-line hole in the ground). In regards to work tasks, they used hot tar to seal roof leaks, cut brush and small trees, and long grasses, and devised a trap door for an unspecified purpose. (The probable explanation is that they put a trap door in the ceiling to allow items to be stashed out of sight).

- A month later, at the end of November there was another visit to Paw Paw on Thanksgiving weekend by a group of 43 persons including MCM members and Boy Scouts. This time, the purpose was hiking, and the group hiked down a steep descent to Paw Pay Tunnel. The account also mentions that the fireplace with its adjustable hood did work, and that the “log book” was not titled “Town Hill Shelter.” While the hike was going on, some adults had prepared a fancy meal of roasted turkeys, sauerkraut, candied sweet potatoes, pumpkin pie, and more. The meal was followed by dancing (including a modified form of the Virginia reel, and ending with cider and doughnuts. And then, as if that were not enough, there was a frosty moonlit hike. Another hike took place the following morning, followed by a lunch of turkey soup and leftovers before the group headed home. (Those early club members did like to party! It may be worth noting that these kinds of hiking celebrations were common for the club in the early decades. They often had Halloween weekends in the Catoctins and New Years weekends at Pine Grove Furnace State Park. Music and square dancing were part of their regular evening entertainment in those days.)

In 1948, there were continuing discussions of the same matters related to the shelter:

- At the January 1948 Council meeting, it was reported that the Marco Club was interesting in using the shelter for a few week-end fishing trips. It was decided that they should request reservations in the usual way.

- At the April 1948 Council, it was announced that the shelter was booked solid through the first week in June. There was discussion of whether to post a sign at the entrance road to the shelter. That suggestion was approved, despite concerns about whether such a sign would attract vandals.

- At the May 1948 Council, Francis Old (the MCM equipment manager) reported that the Marco Club was not using the shelter as much as their lease allowed, which prevented other groups from using the shelter on certain weekends. It was decided to talk with the Marco Club leaders and suggest they reserve it only for special weekends during the hunting and fishing season. Old also reported that the water supply had been condemned by the Allegheny County Water Bureau because it runs for a long distance above ground, increasing the possibility of pollution. Mr. Old would try to find out what corrective measures would be needed.

- At the June 1948 Council, Old stated that the new lease with the state was being reviewed by state’s legal department, and that MCM would wait for its return before signing the Marco Club lease.

The Paw Paw Shelter was a prominent topic in the July – September 1948 Bulletin, which had four different articles related to the Paw Paw shelter:

- The first one described another stop at the shelter on April 3-4, 1948.The group arrived on Saturday and enjoyed a dinner of spaghetti and meatballs. The next day the group hiked near the Cacapon River and Unnecessary Mountain before returning home.

- There was another trip report about a May 29-31 trip to Swallow Falls. The group spent the first night at the Paw Paw Shelter, with dinner and a sing-along. The next day they moved on to hike at Swallow Falls and Muddy Creek Falls in very wet weather, and spent the night in that area before heading directly back to Baltimore.

- There was a third article entitled “What’s The Name of That Shelter?” The author of the article argued that the shelter is located on Town Hill Mountain, in a state forest belonging to the MD Department of Forests and Parks, and the state refers to it as the Town Hill Shelter. Consequently, the unknown author concludes, MCM should call it the Town Hill Shelter. Despite the argument, both names continued to be used by different club officials in the future.

- In this same very busy newsletter, there was also a short discussion entitled Equipment Needed for Town Hill Shelter. The article mentioned the previous thefts of equipment and furnishings and encouraged MCM members to donate their unneeded items for the shelter to be able to handle large groups—examples mentioned include dinnerware, folding cots, mattresses, canisters, cookware, and a stove.

After that, the mentions of the shelter in our records were Council discussions of the same issues:

- At the October 1948 Council meeting, Old reported that the shelter was getting more use than ever before. It had been broken into again, but he did not know what was taken. There was discussion of possible ways to prevent break-ins. It was also mentioned that the Alleghany County Bird Club had the water tested in July and it was found to be safe.

- At the December 1948 Council, Old reported that the Marco Club had offered to make shutters to improve security of the cabin, and MCM accepted the offer.

- At the March 1949 Council, Old reported on two more break-ins. There was damage to window panes and door handles, locks, and the kitchen sink was taken.

- At the April 1949 Council, Old reported that three mattresses had been taken from the shelter and he had decided to resign his position as chairman of the Shelters Committee. There was discussion of why MCM should maintain a shelter that was mostly used by other groups than MCM. The state Forests and Parks Department was unable to give the building any special protection. Formation of a committee was suggested to make recommendations.

The April – June 1949 Bulletin had a trip report of a Thanksgiving weekend trip to Paw Paw, so presumably it occurred in November 1948 and did not get reported in the winter newsletter. Ten hikers, enjoyed a turkey dinner with all the traditional fixings on the first evening. The next day they hiked (slogged) through a drizzling rain that turned into heavy snow, so they returned to Baltimore earlier than planned.

At the May 1949 Council, Old reported that the Shelter Committee recommended abandoning the Paw Paw Shelter because of the multiple factors of vandalism and theft, distance to the shelter, lack of use by MCM members, and lack of a suitable water supply. The Council voted to end the agreement with the state as of June 30, 1949.

At the June 1949 Council, it was reported that MCM had sent a letter to Joseph Kayler, the Director of State Forests and Parks, terminating its tenancy of the shelter. There were discussions of how to dispose of the tools and equipment, as well as the possibility of turning the shelter over to the Maryland Ornithological Society.

The July – September 1949 Bulletin had a report that the use of the shelter by various other groups had increased, providing revenues for MCM’s shelters fund. But the same article stated that MCM’s own use of the shelter was negligible and vandalism was an increasing problem. Therefore, the Council appointed a special committee to make recommendations regarding this shelter and possible future shelters.

Despite the previous statement that MCM use of the shelter was negligible, the same newsletter had a trip report of a May 14-15, 1949 trip to the Town Hill Shelter. After dinner, two members played madrigals and folk tunes on their recorders. Later the conversation turned to modern art before ending at 1:30 a.m. The next day, after working on repairs, they hiked near Sideling Hill Creek, where another MCM contingent met them. The hike leader let the group off trail on a major bushwack until they were caught in a downpour and, eventually, returned to Baltimore earlier than planned.

At the July 1949 Council meeting, Old reported that any moveable equipment had been removed from the shelter. He suggested that the Ornithological Society take it over. He also reported that someone had stolen some mattresses, cots, locks and hooks, etc.

The next newsletter, the October-December 1949 Bulletin, has a two mentions of the decision to stop managing the shelter: “In view of the fact that having disposed of the Paw Paw Shelter, the Mountain Club has only the Dark Hollow lean-to to its credit, that there is a sizable shelters fund to our credit in the bank, that MCM members use shelters extensively, it seems that the line of action should be clear.” The article than invited suggestions from members about possible locations to build a lean-to.

Finally, there is another article in the same newsletter titled, The Last Days of Town Hill – July 16-17, that describes the final trip of a few volunteers to remove MCM’s remaining property from the shelter. The author described in a wry manner how she and her husband were persuaded to attend a “delightful” weekend clearing out the odds and ends. After borrowing a trailer, they encountered setbacks including a flat tire, and later a wheel of the trailer falling off during the drive up the mountain. Eventually, they arrived safely, as did a small crew of other volunteers. The next day, various items such as mattresses, dishware, cookware, disassembled cots, cutlery and curtains were crammed into cars, on top of cars, and in the trailer. The article ends with this appropriate (and rather poetic) epitaph: “With a last long look at our once-glorious Shelter, we chugged slowly away into a gathering downpour.” What happened to the structure after that we don’t know, but it appeared that other groups such as the Ornithological Society and the Marco Club planned to continue using it.

There were no further mentions of the Paw Paw Shelter in Council minutes. Despite the challenges they had encountered, there were still occasional expressions of interest in MCM building its own locked hiking shelter somewhere on public lands, and the Shelters Committee was given an assignment to explore options. The Committee apparently found no promising solutions, and after a few insubstantial updates over the following months, at the March 1950 Council meeting, “Mr. Felton reported that the last meeting of the Shelter Committee resulted in a decision to shelve the idea until the Club displayed more interest.” MCM never did get another hiking retreat for its own use—although the club often reserved shelters in various parks for hiking events.

View Past 90th Anniversary Articles

By clicking on any of the links below, you can view some of the earlier 90th Anniversary articles about aspects of Mountain Club of Maryland history.

Women in the Early Mountain Club

The Disappearance and Rediscovery of the Center Point Knob Plaque

The History of MCM Trail Sections in Pennsylvania

The History of MCM’s Role Maintaining the A.T. in Maryland

Gimme Shelter: A History of MCM Appalachian Trail Shelters

World War II and the Mountain Club: Trains, Trolleys and Trucks

The History of the Hike Across Maryland

MCM and the A.T. in the Cumberland Valley: A Tale of Three Trails

Walking on Wednesdays: The History of MCM Midweek Hikes

Our 90th Anniversary Celebration

MCM will be celebrating our history and success throughout the next year. We have scheduled a series of events:

- Anniversary Hikes: During the upcoming months, we offer a number of hikes that attempt to recreate the routes of early club hikes. If you would like an opportunity to hike in the bootsteps of our club founders, look for the ANNIVERSARY HIKE designation in the hike title or hike description.

- Kinetic Sculpture Parade: On May 4, 2024, an MCM float participatde in the Baltimore Kinetic Sculpture Parade. (For more information about this annual event sponsored by the Baltimore American Visionary Art Museum, click here: Baltimore Kinetic Sculpture Race (kineticbaltimore.com).

- MCM “In-Person” History: Member Reminisces and Stories: starting in May, we invite our members to submit anecdotes or reminisces about their experiences with MCM, which will be shared on our web site.

- MCM Celebratory Gathering: On September 29, 2024, MCM will hold an event at the Howard County Conservancy to celebrate our 90th Anniversary. While the planning is still underway, we anticipate the event will include hiking, food, music, and more STAY TUNED FOR MORE DETAILS.

- Of course, we will also recognize and celebrate our 90th Anniversary during our regular club events such as the Hike Across Maryland in May, the club picnic in June, and the Holiday Party in December.